- A

- A

- A

- ABC

- ABC

- ABC

- А

- А

- А

- А

- А

-

Departments

- Departments

-

Institutes and Centres

-

- Institute of Economics and Utility Regulation

- Institute for Industrial and Market Studies

- Centre for Labour Market Studies

- International Centre of Decision Choice and Analysis

- Centre of Development Institute

- Centre for Financial Research & Data Analytics

- Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence

- Anti-Corruption Centre

-

-

Laboratories

-

- International Laboratory for Macroeconomic Analysis

- International Laboratory of Stochastic Analysis and its Applications

- International Laboratory for Experimental and Behavioural Economics

- Corporate Finance Center

- Laboratory for Banking Studies

- Laboratory for Labour Market Studies

- Laboratory for Sport Studies

- Laboratory for Wealth Measurement

- Project Laboratory for Development of Intellectual Competitions in Economics

- Laboratory for Spatial Econometric Modeling of Socio-Economic Processes in Russia

- Laboratory for Geometric Algebra and Applications

-

- Department of Financial Market Infrastructure

- ICEF

-

Educational Programmes

- Bachelor's Programmes

-

Master's Programmes

-

- Economics and Economic Policy

- Agrarian Economics

- Stochastic Modeling in Economics and Finance (Previously, Master's in Statistical Modelling and Actuarial Science)

- Statistical Analysis in Economics

- Economic Analysis (Online)

- Strategic Corporate Finance

- Financial Markets and Institutions

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Engineering

- Master of Business Analytics (Online)

- Investments in Financial Markets (Online)

-

- Doctoral Programmes

-

Faculty

109028, Moscow,

11 Pokrovsky Boulevard,

Room Т-614

Phone: (495) 628-83-68

email: fes@hse.ru

Founded in 1992, the HSE Faculty of Economics is the university’s oldest faculty. In the years since it was founded, it has gained a reputation as Russia’s leader in terms of higher economic education.

A fundamental education in modern economic theory and mathematics is combined with the study of applied disciplines, such as taxation, budget policies and processes, financial management and other related fields.

Tarasova K., Gracheva D., Talov D. et al.

Studies in Higher Education. 2025. No. 1. P. 1-16.

In bk.: Advances in Computer Graphics: 41st Computer Graphics International Conference, CGI 2024, Geneva, Switzerland, July 1–5, 2024, Proceedings, Part III. Vol. 15340. Springer, 2025. P. 336-348.

Series FE "Financial Economics"". WP BRP. HSE University , 2025. No. WP BRP 97.

109028, Moscow,

11 Pokrovsky Boulevard,

Room Т-614

Phone: (495) 628-83-68

email: fes@hse.ru

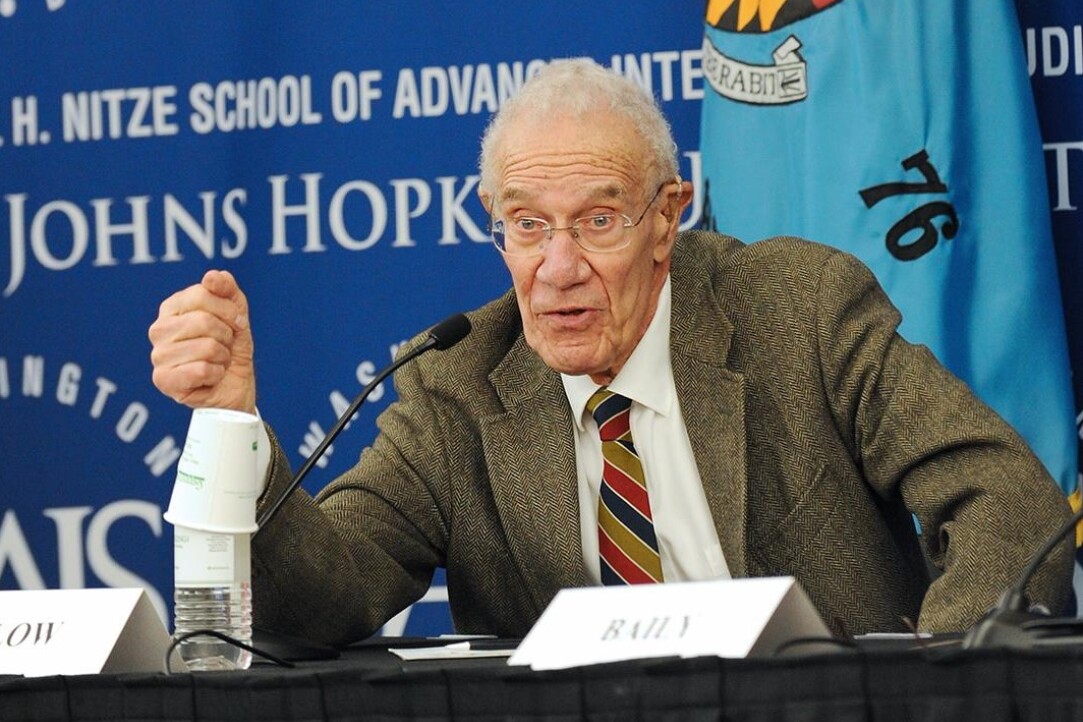

In memory of Robert Solow

Professor Sergei Pekarsky, Dean of the Faculty of Economics Sciences:

— These words sound strange for a Nobel Prize winner, but I say Robert Solow is more than just a Nobel Prize winner. Like the name of J.M.Keynes, Solow's name will be remembered by anyone who has studied economics. However, Robert Solow's contributions to science are not limited to the basic theory of economic growth. And it is completely impossible to explain it in a few lines. A decade and a half ago, I was lucky enough to attend a lecture by Robert Solow at I.S.E.O Summer School and took the opportunity to ask him a question. The question was a very general and simple one, about the prospects for the development of endogenous economic growth theory. The answers from scientists who contributed to science 50 years ago were astonishing in their depth and complexity. These were not just common words.

But what I remember most of all is something else Robert Solow said in response to a question about the role of econometrics and modern methods of working with data. Repeat from memory. "Half a century ago, my colleagues and I didn't have the same data processing skills as we do today. That's why we thought first and then calculated." Like most of my colleagues, I also didn't have the same data processing skills that we have today. I am excited about the prospects of using econometrics, machine learning techniques, and artificial intelligence. But I would like all economics students (not just economists) to remember the words of this great scientist.

Vladimir Avtonomov, Professor, Faculty of Economics Sciences:

— Robert Solow made very significant contributions to the development of economic sciences. It is usually associated with the creation of the so-called neoclassical model of economic growth. It must be said that after the Second World War, the Keynesian paradigm was the main one in the study of macroeconomics, but Keynes did not study growth, he dealt with the cycle, and he did not touch upon the problems of long-term economic growth. There have been attempts to create neo-Keynesian growth models, for example by Roy Harrod and Evsey Domar. But Robert Solow was one of the first (Trevor Swan was another) to propose his theory, based on neoclassical economic theory, where growth is considered to be a derivative of the basic factors, capital and labor. And it is assumed that in the process of growth, it is possible, in particular, to replace capital with labor and vice versa. This is the main advantage of neoclassical theory. Previously, neoclassicism was not introduced into macroeconomics; it dominated at the microeconomic level, and at the “macro” level it was mainly Keynesian theory. Solow was in this sense its main spokesman and herald of neoclassical growth theory.

Then, when the macroeconomic function of economic growth he created was evaluated on the data, it turned out that the variables capital and productivity of capital and labor and labor productivity explain, in fact, not everything, but somewhere around half of all economic growth. What remains? Solow attributed this remainder to scientific and technological progress. This famous term “Solow residual” began the focus of economists on the development of science, on how it affects growth and other economic processes. Solow was the first to pose this problem.

But it must be said that Robert Solow was a very versatile person. At first he opposed the Keynesians, for neoclassics. And when the time came for the so-called micro-based macroeconomics, in the 70-80s, when new macroeconomic theories based on rational expectations arose, Solow did not agree with them either. He believed that the theories of Lucas, Sargent, and Wallace were too abstract and departed too far from reality. And even despite the fact that these views, in general, won and spread widely, Solow did not abandon attempts to argue with them, and in scientific journals and in the general press he severely criticized them.

I have to say that when I happened to be at MIT in Boston once in my life, I looked at the schedules of various courses and saw that Robert Solow was teaching a first-year introductory course for economics. Do you understand? Nobel laureate, the greatest theorist of growth - and is dedicated to conveying the essence of economics to freshmen. I think that says a lot about him. He tried never to break away from the substantive essence of what was happening in the economy. He did not succumb to the game of purely technical techniques that allow the creation of theories. This was a man who always tried to ensure that the macroeconomic theory he was studying did not break away from reality.

For example, there was also a period when he was included in the discussion with John Kent Galbraith and Robin Maris, who had a more verbal and more social theory of the large corporation. They tried to create a theory that competitive capitalism was being replaced by mega-corporations, within which there was planning. That is, there is a transition from a market system to a planned system. Solow was against it and also took part in this discussion. That is, I would say that Robert Solow was one of the most broad-minded economists of our era. Absolutely everything was clear to him: neoclassics, mathematics, models, and at the same time phenomena that are in the socio-economic field. I'm afraid that he was the last Great Economist we have now lost.

Sergei Merzlyakov, First Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Economics Sciences:

— In 2010, as a graduate student, I went to the I.S.E.O Summer School, which until recently was chaired by Robert Solow. It is a renowned event where Nobel laureates speak, and keynote speakers that year included George A. Akerlof, Michael A. Spence, and Robert M. Solow. This was almost 14 years ago, and Robert Solow was already old then. But it was he, and not his younger colleagues, who attracted the attention of all summer school participants. His lecture captivated the audience with its clarity and wit, and in a free dialogue with the audience, Robert Solow demonstrated that he was well versed in the current scientific agenda.

Among other things, Robert Solow expressed skepticism about the development of macroeconomics and shared his vision of its further development. The fact is that 2010 was the year after the global financial crisis, for which many economists felt responsible because they could not predict the crisis in advance, so at that moment a rethinking of where exactly macroeconomic science should move was required.

And if many years ago Robert Solow had a heated and witty debate about the development of economic science with Keynesians and especially with monetarists, then in 2010 his words were perceived rather as a reconciliation of various macroeconomic schools in an attempt to find the keys to solving modern macroeconomic problems.

Dmitry Veselov, Deputy Dean of the Faculty of Economics Sciences:

— In 1956 Robert Solow proposed a model that formed the basis of modern economists' ideas about long-term economic growth. Several generations of researchers have passed, but the Solow model remains key in textbooks or courses in macroeconomics. This is where courses in the theory of economic growth begin.

“Not every simple model is a good one,” says Robert Solow in an interview. The peculiarity of the Solow model is its simplicity and depth at the same time. As in the case of an ideal work of art, Solow leaves only the essentials in the economic growth model; in the limit, the model is reduced to only one dynamic equation. At the same time, it has the ability to explain long-term patterns and answer one of the key practical questions of growth theory: can investment in physical capital guarantee sustainable growth.

The result obtained by Solow has a similar impact on the understanding of economic growth, as the transition from a geocentric to a heliocentric system of the world in astronomy. Solow convincingly shows that the accumulation of physical capital is not sufficient to ensure sustainable growth in per capita income, and the exogenous component not associated with capital accumulation is the most important.

In the field of theory, the Solow model opened up a new universe for the researcher. If physical capital fails to explain economic growth, as the Solow model suggests, what is the key ingredient? In the following decades, economists developed a range of models reflecting the role of education, technological progress, infrastructure, institutions and culture as key determinants of long-term growth. Many of these models are based on the Solow model or can be reduced to it under certain assumptions.

Robert Solow's contribution is unique not only in the theory but also in the empirics of growth. He proposed a method that is still key to describing the sources of long-term growth. His 1956 paper opened up a broad new field of knowledge, the development of which he followed with interest, discussing in his subsequent works the issues that have confronted macroeconomic theory down to the present day.

It is not only Robert Solow's academic legacy that is admirable, but also his ability to look critically at theory and remain an intellectual leader throughout the long years of his life.

- About

- About

- Key Figures & Facts

- Sustainability at HSE University

- Faculties & Departments

- International Partnerships

- Faculty & Staff

- HSE Buildings

- Public Enquiries

- Studies

- Admissions

- Programme Catalogue

- Undergraduate

- Graduate

- Exchange Programmes

- Summer Schools

- Semester in Moscow

- Business Internship

-

https://elearning.hse.ru/en/mooc/

Massive Open Online Courses

-

https://www.hse.ru/en/visual/

HSE Site for the Visually Impaired

-

http://5top100.com/

Russian Academic Excellence Project 5-100

- © HSE University 1993–2025 Contacts Copyright Privacy Policy Site Map

- Edit